2025-12-31 Posted by TideChem view:240

Since its proposal by Bruce Merrifield in 1963, solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) has fundamentally transformed the research paradigm of peptide chemistry. Its development can be divided into three stages:

(1) 1960–1980: Utilizing polystyrene‑divinylbenzene copolymers as solid supports and the Boc (tert‑butoxycarbonyl) protection strategy, the first automated synthesizer was developed.

(2) 1980–2000: The Fmoc (fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl) protection strategy gradually matured and became mainstream due to its milder deprotection conditions and better functional‑group compatibility.

(3) 2000–present: The application of novel resins (e.g., Rink Amide, Wang Resin), efficient coupling reagents (e.g., HATU, PyBOP), and continuous‑flow technology has continuously improved synthetic efficiency and length limits.

SPPS is widely used for the synthesis of peptide drugs owing to its high amino‑acid utilization, high degree of automation, high synthetic efficiency, operational simplicity, and reliability. However, it also has some drawbacks, including side reactions during the process, amino‑acid deletions and insertions, amino‑acid racemization, β‑elimination of amino‑acid residues, and the formation of diketopiperazines (DKPs) and Aspartimide.

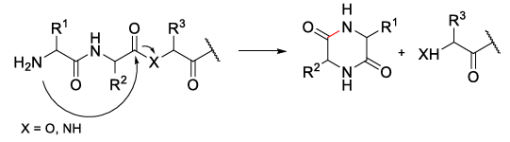

The formation of DKP (2,5-diketopiperazine) is one of the most common side reactions in SPSS, posing a significant challenge to efficient peptide production. This side reaction typically occurs under alkaline conditions and is particularly prone to occur in Fmoc-Wang resin-based synthesis systems. As illustrated in Fig1, the mechanism of DKP formation involves the following process: after removal of the Fmoc protecting group from the second amino acid, its free α-NH₂ group nucleophilically attacks the carbonyl group of the amide bond (or ester bond) of the first amino acid, leading to cleavage of the peptide bond (or ester bond), followed by cyclization to form the six-membered diketopiperazine structure, which subsequently detaches from the peptide chain.

Fig1. Mechanism of DKP Formation.

DKP formation exhibits significant sequence dependence. This side reaction occurs more readily when the peptide bond between Xaa1-Xaa2 tends to adopt a cis conformation rather than the more common trans conformation. Specific scenarios include:

To suppress DKP side reactions, multiple strategies can be employed, including the use of less reactive coupling reagents, lowering the reaction temperature, or optimizing the deprotection system. For example, employing 2% DBU/5% piperazine/NMP as the Fmoc deprotection reagent, compared to the traditional 20% piperidine/DMF system, can significantly reduce the extent of DKP side reactions.

During peptide synthesis, serine (Ser), threonine (Thr), cysteine (Cys), and methionine (Met) may undergo acid- or base-catalyzed β-elimination reactions, yielding dehydroalanine (ΔAla), β-methyl-ΔAla, or thiocysteine, respectively. The resulting α,β-dehydroamino acid residues can further undergo addition reactions with the side chains of lysine (Lys), cysteine (Cys), or histidine (His), while thiocysteine may induce disulfide bond reshuffling within the peptide. Additionally, the hydroxyl or thiol groups in the side chains of Ser, Thr, Cys, and Met promote intermolecular hydrophobic aggregation or the formation of secondary structures in peptide chains, with β-sheet structures being the most prominent.

Oxazolidine derivatives derived from Ser/Thr and thiazolidine derivatives derived from Cys (Pseudoproline) favor the formation of cis-amide bonds due to their five-membered ring structure. This introduces a "kink" conformation into the peptide backbone, effectively suppressing hydrophobic aggregation and β-sheet formation, thereby significantly improving peptide synthesis efficiency.

Taking GLP-1 analogs such as semaglutide and tirzepatide as examples, these antidiabetic and weight-loss drugs feature long amino acid sequences containing multiple Thr and Ser residues. In SPPS, incorporating Ser and Thr pseudodipeptide building blocks can effectively enhance synthesis quality and yield. Tide Chem consistently supplies various Ser and Thr pseudodipeptide raw materials and offers customization services, providing stable and reliable chemical support for the efficient preparation of complex peptides.

Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-Ser(Psi(Me,Me)Pro)-OH(CAS:1425938-63-1)

Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-Ser(Psi(Me,Me)Pro)-OH(CAS:1000164-43-1)

Fmoc-Tyr(tBu)-Ser(Psi(Me,Me)Pro)-OH(CAS:878797-09-2)

Fmoc-Pro-Ser(Psi(Me,Me)Pro)-OH(CAS:1425938-64-2)

Fmoc-Gly-Thr(Psi(Me,Me)Pro)-OH(CAS:1262308-49-5)

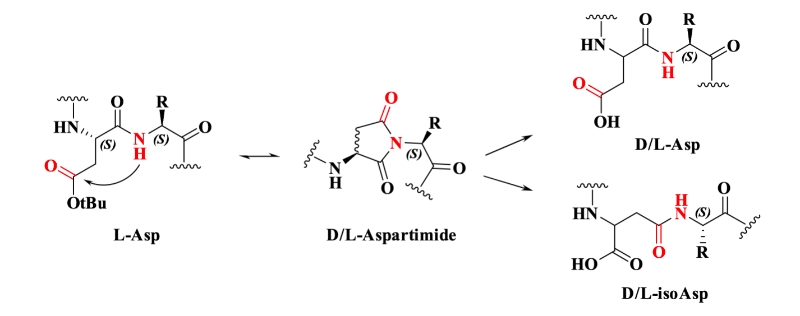

Aspartimide formation is also one of the most common side reactions in SPSS. The reaction mechanism is as follows: under strongly alkaline conditions, the amide bond in the peptide backbone can undergo deprotonation to form a nucleophilic amide anion. This anion subsequently attacks the electrophilic carbonyl group of the side-chain carboxylate ester, leading to the formation of a succinimide intermediate. This intermediate is highly prone to hydrolysis and ring-opening, generating D/L-Asp and its isomer D/L-isoAsp, thereby introducing impurities.

Fig2. Mechanism of Aspartimide Formation.

The aspartimide cyclization reaction exhibits significant dependence on the amino acid sequence. The following sequences are particularly prone to this side reaction: -Asp-Gly-, -Asp-Asp-, -Asp-Asn-, -Asp-Arg-, -Asp-Thr-, -Asp-Cys-.

The generation of isomeric impurities significantly increases the difficulty of detection and purification of the target peptide. In terms of side-chain protecting group selection for aspartic acid residues, the commonly used Asp(OtBu) provides limited suppression of cyclization. In contrast, employing protecting groups with greater steric hindrance or specific stabilizing effects, such as Asp(ODmab) and Asp(OMpe), can effectively prevent the occurrence of aspartimide side reactions.

Yang, Yi, and Lena Hansen. "Optimized Fmoc-removal strategy to suppress the traceless and conventional diketopiperazine formation in solid-phase peptide synthesis." ACS omega 7.14 (2022): 12015-12020.

Yang, Yi. Side reactions in peptide synthesis. Academic Press, 2015.

Wöhr, Torsten, et al. "Pseudo-prolines as a solubilizing, structure-disrupting protection technique in peptide synthesis." Journal of the American Chemical Society 118.39 (1996): 9218-9227.

Grassi, Luigi, and Chiara Cabrele. “Susceptibility of protein therapeutics to spontaneous chemical modifications by oxidation, cyclization, and elimination reactions.” Amino acids vol. 51,10-12 (2019): 1409-1431. doi:10.1007/s00726-019-02787-2.

Behrendt, Raymond et al. “Advances in Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis.” Journal of peptide science : an official publication of the European Peptide Society vol. 22,1 (2016): 4-27. doi:10.1002/psc.2836.